D Never Say Never Again Video Game

![]()

Never Say Never Again is the second James Bond theatrical film not produced by EON Productions and the second film adaptation of the story Thunderball. Released in 1983, it stars Sean Connery in his seventh and final film performance as British Secret Service agent James Bond. It was released theatrically by Warner Bros.

The film is not considered part of the canon of the Bond film franchise from EON Productions and United Artists and is not produced by Albert R. Broccoli, despite it currently being handled by the official film series distributor, MGM. MGM acquired the distribution rights in 1997 after their acquisition of Orion Pictures. The film also marks the culmination of a long legal battle between United Artists and Kevin McClory. Its release opposite the franchise Bond film Octopussy (starring Roger Moore) quickly led the media to dub the situation the "Battle of the Bonds".

In November 2013, the McClory Estate and EON Productions reached an agreement transferring all rights to Fleming's Thunderball, the organization of SPECTRE, and the character of Ernst Stavro Blofeld to EON.

Plot summary

Being the second adaptation of the novel Thunderball, Never Say Never Again follows a similar plotline to the earlier film, but with some differences.

The film opens with a middle-aged, yet still athletic James Bond making his way through an armed camp in order to rescue a girl who has been kidnapped. After killing the kidnappers, Bond lets his guard down, forgetting that the girl might have been subject to Stockholm syndrome (in which a kidnapped person comes to identify with his/her kidnappers) and is stabbed to death by her. Or so it seems.

In fact, the attack on the camp is nothing more than a field training exercise using blank ammunition and fake knives, and one Bond fails because he ends up "dead". A new M is now in office, one who sees little use for the 00-section. In fact, Bond has spent most of his recent time teaching, rather than doing, a fact he points out with some resentment.

Feeling that Bond is slipping, M orders him to enroll in a health clinic in order to "eliminate all those free radicals" and get back into shape. While there, Bond discovers a mysterious nurse, Fatima Blush, and her patient, who is wrapped in bandages. His suspicions are aroused even further when a thug (Lippe) tries to kill him.

Blush and her charge, an American Air Force pilot named Jack Petachi, are in fact operatives of SPECTRE, a criminal organization run by Ernst Stavro Blofeld. Petachi has undergone an operation to alter one of his retinas to match the retinal pattern of the American President. Using his position as a pilot, and the president's eye pattern to circumvent security, Petachi infiltrates an American military base in England and orders the dummy warheads in two cruise missiles replaced with two live nuclear warheads, which SPECTRE captures and uses to extort billions of dollars from the governments of the world.

M reluctantly reactivates the 00 section, and Bond is assigned the task of tracking down the missing weapons, beginning with a rendezvous with Domino Petachi, the pilot's sister, who is kept a virtual prisoner by her lover, Maximillian Largo. Bond pursues Largo and his yacht to the Bahamas, where he engages Domino, Fatima Blush, and Largo in a game of wits and resources as he attempts to derail SPECTRE's scheme.

Changes to the Bond universe

The film makes a few changes to the James Bond universe. MI6 is shown to be underfunded and understaffed, particularly with regards to Q-Branch, and the character Q is referred to by the name "Algernon", and is presumably a different individual than the Q in the official Bond films (whose name is Major Boothroyd). The film also appears to take place in an "alternate universe" in which none of the events of You Only Live Twice, On Her Majesty's Secret Service, Diamonds Are Forever and the opening sequence of For Your Eyes Only have occurred, since Blofeld is alive and apparently previously unknown to Bond and MI6. Despite sharing many basic similarities with Thunderball, the course of events throughout the film are different enough for it to be more than a direct remake, and the action clearly takes place at a much later date (contemporary with the film's production).

The film is notable for depicting Felix Leiter, Bond's CIA colleague, as an African-American, something which would not occur in the EON series until Casino Royale in 2006. The film also makes a major departure from official continuity by ending with Bond indicating his intention to retire from MI6 - while Bond had considered retirement in On Her Majesty's Secret Service, he is shown to be unsure of the decision and later chooses to stay with the service. In the scene where Bond states his intention to quit, Connery breaks the fourth wall by winking at the camera; while this is incorrectly considered by many as being unique to this film, George Lazenby was in fact the first Bond to break the fourth wall almost 15 years earlier when he told the audience, "This never happened to the other fellow" (referring to Connery, the man he had replaced as Bond).

Production

Never Say Never Again had its origins in the early 1960s, following the controversy over the 1961 Thunderball novel.[1] Fleming had worked with independent producer Kevin McClory and scriptwriter Jack Whittingham on a script for a potential Bond film, to be called Longitude 78 West,[2] which was subsequently abandoned because of the costs involved.[3] Fleming, "always reluctant to let a good idea lie idle",[3] turned this into the novel Thunderball, for which he did not credit either McClory or Whittingham;[4] McClory then took Fleming to the High Court in London for breach of copyright[4] and the matter was settled in 1963.[2] After Eon Productions started producing the Bond films, it subsequently made a deal with McClory, who would produce Thunderball, and then not make any further version of the novel for a period of ten years following the release of the Eon-produced version in 1965.[5]

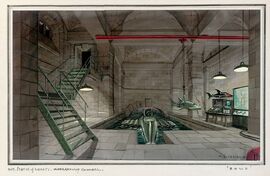

Warhead (1978) concept artwork - interior of the Statue of Liberty depicting docking chamber with a submarine, and a robot 'Hammerhead' shark hanging.

In the mid-1970s McClory again started working on a project to bring a Thunderball adaptation to production and, with the working title Warhead, he brought writer Len Deighton together with Sean Connery to work on a script.[6] The script ran into difficulties after accusations from Eon Productions that the project had gone beyond copyright restrictions, which confined McClory to a film based on the Thunderball novel only, and once again the project was deferred.[5]

Towards the end of the 1970s developments were reported on the project under the name James Bond of the Secret Service,[5] but when producer Jack Schwartzman became involved and cleared a number of the legal issues that still surrounded the project[1] he brought on board scriptwriter Lorenzo Semple, Jr.[7] to work on the screenplay. Connery was unhappy with some aspects of the work and asked Tom Mankiewicz, who had rewritten Diamonds Are Forever, to work on the script; however Mankiewicz declined as he felt he was under a moral obligation to Cubby Broccoli.[8] Connery then hired British television writers Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais[9] to undertake re-writes, although they went uncredited for their efforts because of a restriction by the Writers Guild of America.[6]

The film underwent one final change in title: after Connery had finished filming Diamonds Are Forever he had pledged that he would "never" play Bond again.[6] Connery's wife, Micheline, suggested the title Never Say Never Again, referring to her husband's vow[10] and the producers acknowledged her contribution by listing on the end credits "Title "Never Say Never Again" by: Micheline Connery". A final attempt by Fleming's trustees to block the film was made in the High Court in London in the spring of 1983, but this was thrown out by the court and Never Say Never Again was permitted to proceed.[5]

Cast and crew

When producer Kevin McClory had first planned the film in 1964 he held initial talks with Richard Burton for the part of Bond,[11] although the project came to nothing because of the legal issues involved. When the Warhead project was launched in the late 1970s, a number of actors were mentioned in the trade press, including Orson Welles for the part of Blofeld, Trevor Howard to play M and Richard Attenborough as director.[6]

In 1978 the working title James Bond of the Secret Service was being used and Connery was in the frame once again, potentially going head-to-head with the next Eon Bond film, Moonraker.[12] By 1980, with legal issues again causing the project to founder,[6] Connery thought himself unlikely to play the role, as he stated in an interview in the Sunday Express: "when I first worked on the script with Len I had no thought of actually being in the film".[13] When producer Jack Schwartzman became involved, he asked Connery to play Bond; Connery agreed, asking (and getting) a fee of $3 million, ($7 million in 2016 dollars) a percentage of the profits, as well as casting and script approval.[6] Subsequent to Connery reprising the role, the script has several references to Bond's advancing years – playing on Connery being 52 at the time of filming[6] – and academic Jeremy Black has pointed out that there are other aspects of age and disillusionment in the film, such as the Shrubland's porter referring to Bond's car ("They don't make them like that anymore."), the new M having no use for the 00 section and Q with his reduced budgets.[14]

For the main villain in the film, Maximillian Largo, Connery suggested Klaus Maria Brandauer, the lead of the 1981 Academy Award-winning Hungarian film Mephisto.[7] Through the same route came Max von Sydow as Ernst Stavro Blofeld,[15] although he still retained his Eon-originated white cat in the film.[16] For the femme fatale, director Irvin Kershner selected former model and Playboy cover girl Barbara Carrera to play Fatima Blush – the name coming from one of the early scripts of Thunderball.[6] Carrera's performance as Fatima Blush earned her a Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress,[17] which she lost to Cher for her role in Silkwood.[18] Micheline Connery, Sean's wife, had met up-and-coming actress Kim Basinger at a hotel in London and suggested her to Connery, which he agreed upon.[6] For the role of Felix Leiter, Connery spoke with Bernie Casey, saying that as the Leiter role was never remembered by audiences, using a black Leiter might make him more memorable.[7] Others cast included comedian Rowan Atkinson, who would later parody Bond in his role of Johnny English.[19]

Former Eon Productions' editor and director of On Her Majesty's Secret Service, Peter R. Hunt, was approached to direct the film but declined due to his previous work with Eon.[20] Irvin Kershner, who had achieved success in 1980 with The Empire Strikes Back was then hired. A number of the crew from the 1981 film Raiders of the Lost Ark were also appointed, including first assistant director David Tomblin, director of photography Douglas Slocombe and production designers Philip Harrison and Stephen Grimes.[7] [15]

Filming

The Kingdom 5KR which acted as Largo's ship, the Flying Saucer

Filming for Never Say Never Again began on 27 September 1982 on the French Riviera for two months[6] before moving to Nassau, the Bahamas in mid-November[7] where filming took place at Clifton Pier, which was also one of the locations used in Thunderball.[6] The Spanish city of Almería was also used as a location.[21] Largo's Palmyran fortress was actually historic Fort Carré in Antibes.[22] For Largo's ship, the Flying Saucer, the yacht Nabila, owned by Saudi billionaire, Adnan Khashoggi, was used. The boat, now owned by Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal, has subsequently been renamed the Kingdom 5KR.[23] Principal photography finished at Elstree Studios where interior shots were filmed.[6] Elstree also housed the Tears of Allah underwater cavern, which took three months to construct.[6] Most of the filming was completed in the spring of 1983, although there was some additional shooting during the summer of 1983.[7]

Production on the film was troubled,[15] with Connery taking on many of the production duties with assistant director David Tomblin.[6] Director Irvin Kershner was critical of producer Jack Schwartzman, saying that whilst he was a good businessman, "he didn't have the experience of a film producer".[6] After the production ran out of money, Schwartzman had to fund further production out of his own pocket and later admitted he had underestimated the amount the film would cost to make.[15]

Steven Seagal, who was the fight choreographer for this film, broke Connery's wrist while training. On an episode of The Tonight Show with Jay Leno, Connery revealed he did not know his wrist was broken until over a decade later.[24]

Many of the elements of the Eon-produced Bond films were not present in Never Say Never Again for legal reasons. These included the gun barrel sequence, where a screen full of 007 symbols appeared instead, and similarly there was no "James Bond Theme" to use, although no effort was made to supply another tune.[7] A pre-credits sequence was filmed but not used;[15] instead the film opens with the credits run over the top of the opening sequence of Bond on a training mission.[6]

Music

The music for Never Say Never Again was written by Michel Legrand, who composed a score similar to his work as a jazz pianist.[25] The score has been criticised as "anachronistic and misjudged",[6] "bizarrely intermittent"[15] and "the most disappointing feature of the film".[7] Legrand also wrote the main theme "Never Say Never Again", which featured lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman—who had also worked with Legrand in the Academy Award winning song, "The Windmills of Your Mind"[26]—and was performed by Lani Hall[7] after Bonnie Tyler, who disliked the song, had reluctantly declined.[27]

Phyllis Hyman also recorded a potential theme song, written by Stephen Forsyth and Jim Ryan, but the song—an unsolicited submission—was passed over given Legrand's contractual obligations with the music.[28]

Cast and Characters

Crew

MGM DVD cover.

- Directed by: Irvin Kershner

- Screenplay by: Lorenzo Semple Jr.

- Produced by: Jack Schwartzman, Kevin McClory (executive), Michael Dryhurst (associate)

- Cinematography by Douglas Slocombe

- Music composed by: Michel Legrand

Comic Adaptation

Argentinean publisher Editora Columba, who published several original Spanish-language James Bond film adaptations in various D'artagnan comic magazines during the '60s and '70s, adapted Never Say Never Again in 1984.

Trivia

- This is the only Bond movie to be directed by an American. The film's director, Irvin Kershner, had previously directed Sean Connery in A Fine Madness.

- The movie title comes from Sean Connery's statement when asked if he would ever play Bond again after Diamonds Are Forever, to which he replied "Never Again".

- The Flying Saucer, Largo's ship, is a translation of "the Disco Volante", the name of Largo's ship in Thunderball. In this film, the Disco Volante is a formidable vessel clearly based on a military cruiser hull, with a helipad and scale which dramatically dwarf the vessel present in the official film continuity. The Disco is still the base of underwater operations by Largo. In real life, the ship used in long shots was known as the "Nabila" and was built for Saudi billionaire, Adnan Kashoggi.

- The casino where Bond and Largo go head to head in a videogame was called Casino Royale.

- This scene also prevented author John Gardner from having a somewhat similar scene involving Bond playing a computer game over a LAN in Gardner's novel Role of Honour. Bond was supposed to be playing a simulation of "The Battle of Waterloo", this was later changed to a different type of game involving "The Battle of Bunker Hill". Interestingly, the Battle of Waterloo would also play a part in the later official Bond film, The Living Daylights.

- Originally, both this film and Octopussy were to be released to theatres simultaneously, which led to a brief flurry of media activity regarding the "Battle of the Bonds". Ultimately, it was decided to separate the two release dates.

- McClory originally planned for the film to open with some version of the famous "gunbarrel" opening as seen in the official Bond series, but ultimately the film opens with a screenful of "007" symbols instead. When the soundtrack for the film was released on CD, it included a piece of music composed for the proposed opening.

- Klaus Maria Brandauer, who played Largo, was originally cast as Marko Ramius in The Hunt for Red October; the role eventually went to Connery.

- Rowan Atkinson made his film debut in this movie. Atkinson, who later became famous for the Mr. Bean comedy series, played a British agent in this movie, the bungling Nigel Small-Fawcett. Later he would play a James Bond parody in Johnny English.

See also

- The controversy over Thunderball.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pfeiffer, Lee; Worrall, Dave (1998). The Essential Bond. London: Boxtree Ltd, p.213. ISBN 978-0-7522-2477-0.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Poliakoff, Keith (2000). "License to Copyright – The Ongoing Dispute Over the Ownership of James Bond". Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal 18: 387–436. Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. Retrieved on 3 September 2011. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Poliakoff (2000)" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray, pp.226. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Yours Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, p.198-99. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Chapman, James (2009). Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. New York: I.B. Tauris, p.184. ISBN 978-1-84511-515-9.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books, pp.152-56. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd, p.240-43. ISBN 1-85283-234-7.

- ↑ Mankiewicz, Tom; Crane, Robert (2012). My Life as a Mankiewicz. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, p.150. ISBN 978-0-8131-3605-9.

- ↑ La Frenais, Ian (1936–) and Clement, Dick (1937–). Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved on 3 September 2011.

- ↑ Dick, Sandra. "Eighty big facts you must know about Big Tam", 25 August 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ "A Rival 007 – It Looks Like Burton", 21 February 1964, p. 13.

- ↑ Davis, Victor. "Bond versus Bond", 29 July 1978, p. 4.

- ↑ Mann, Roderick. "Why Sean won't now be back as 007 ...", 23 March 1980, p. 23.

- ↑ Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press, p.58. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Smith, Jim (2002). Bond Films. London: Virgin Books, pp.193-99. ISBN 978-0-7535-0709-4.

- ↑ Chapman, James (2009). Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. New York: I.B. Tauris, p.135. ISBN 978-1-84511-515-9.

- ↑ Barbara Carrera. Official Golden Globe Award Website. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved on 2 September 2011.

- ↑ Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture. Official Golden Globe Award Website. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved on 3 September 2011.

- ↑ Johnny English. Penguin Readers Factsheets (2003). Retrieved on 5 September 2011.

- ↑ "Director Peter Hunt – "On Her Majesty's Secret Service"", Retrovision. Retrieved on 5 September 2011.

- ↑ Armstrong, Vic (7 May 2011). I'm the real Indiana (when I'm not busy being James Bond or Superman). Daily Mail.

- ↑ Reeves, Tony (2001). The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations. Chicago: A Cappella, p.134. ISBN 978-1-55652-432-5.

- ↑ Salmans, Sandra. "Lavish Lifestyle of a Wheeler-Dealer", 22 February 1985. Retrieved on 6 September 2011.

- ↑ Kurchak, Sarah (12 October 2015). Did Steven Seagal Break Sean Connery's Wrist with Aikido?. Vice.com. Retrieved on 24 November 2015.

- ↑ Bettencourt, Scott (1998). "Bond Back in Action Again". Film score monthly .

- ↑ Error on call to Template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- ↑ The Bat Segundo Show: Bonnie Tyler (12 September 2008). Tyler also discusses this in the documentary James Bond's Greatest Hits.

- ↑ Burlingame, Jon (2012). The Music of James Bond. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.112. ISBN 978-0-19-986330-3.

External links

- Never Say Never Again (1983) at IMDb

- MGM's page on the film

| James Bond films |

|---|

| Sean Connery Dr. No (1962) • From Russia with Love (1963) • Goldfinger (1964) • Thunderball (1965) • You Only Live Twice (1967) • Diamonds are Forever (1971) |

| George Lazenby On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969) |

| Roger Moore Live and Let Die (1973) • The Man with the Golden Gun (1974) • The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) • Moonraker (1979) • For Your Eyes Only (1981) • Octopussy (1983) • A View to a Kill (1985) |

| Timothy Dalton The Living Daylights (1987) • Licence to Kill (1989) |

| Pierce Brosnan GoldenEye (1995) • Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) • The World Is Not Enough (1999) • Die Another Day (2002) |

| Daniel Craig Casino Royale (2006) • Quantum of Solace (2008) • Skyfall (2012) • Spectre (2015) • No Time To Die (2021) |

| Unofficial films Casino Royale (1954) • Casino Royale (1967) • Never Say Never Again (1983) |

Source: https://jamesbond.fandom.com/wiki/Never_Say_Never_Again_(film)

0 Response to "D Never Say Never Again Video Game"

Post a Comment